This post was last updated on October 5th, 2022 at 08:53 am.

Accounting software that’s fund based versus non-fund based — at its core are two different animals. It would be like comparing a lion to a mountain cat. These big cats are similar but at their core, they are different in everything from habitat to how they hunt. Lions hunt in a pride where hunting is typically done by the female lions. On the other hand, mountain lions hunt in solitary as most big cats do.

Accounting in all of its various forms have similarities like debits and credits. Additionally, they all follow certain philosophies like the accounts have to remain in balance using double-entry accounting or the accounts in the chart of accounts (CoA) should be listed in order starting with assets, liabilities, revenues, and expenses.

We are going to outline in detail fund accounting and its core differences to the more popular for-profit accounting software. In this post, we will discuss how checkbooks and revenues happen in fund accounting software versus for-profit software.

Receiving Income in a For-profit Organization

In this section, we will receive money into the checkbook using one or more revenue accounts. We will also go over an example of why this method fails when it comes to accountability questions on how much money was received for designated purposes.

Receiving income via for-profit system using one revenue account

Let’s first review the easier for-profit scenario using the illustration below. For-profit organizations concentrate on profitability, unlike nonprofits, which focus on accountability. In a for-profit setup, the accounting transaction (ie. debit and credit) is very simple as shown in the illustration’s table below.

In a for-profit organization, the money received from doing work is not broken down for accountability purposes. For example, say you are an auto garage that does oil changes, brakes, engine repair, and so on. The garage receives payments from customers throughout the day and it totals $3,750.00 for the day’s deposit.

However, the garage did multiple brake jobs, oil changes, and one engine repair. You will notice that all the money is in one lump sum when entered into the auto garage’s accounting books. The table shows this very simple transaction with two disbursements – ie the credit to the revenue and debit to the checkbook mentioned earlier.

For-profit systems fail to answer accountability questions

Some questions the garage can’t answer with a for-profit set up.

- How much money did we make on oil changes today?

- Or, how much did we make on brake jobs for the day?

- How much did we make in engine repairs all year?

- Are we making more money on oil changes or brake jobs?

- How about engine repair revenue compared to oil changes?

These questions would require a complete audit of every transaction that comes into the revenue account to review the service(s) performed and how much it was, individually. That would mean auditing thousands of transactions to answer pretty simple questions. These are the kind of accountability questions that churches must answer and why they use a different accounting methodology and a different accounting software.

Why does for-profit system fail in accountability questions?

When all the money is combined into one revenue account with no other annotations, the garage can’t tell how much they made on oil changes, brake jobs, or engine repairs separately. All the revenue is lumped into one pile of money instead of separating it into different categories. Because a for-profit company is only concerned with ‘profitability’ they aren’t concerned with how much they made just doing oil changes. They are more concerned with – did they make more money than last year. That is why these organizations are called ‘for-profit’.

Doesn’t multiple revenue accounts help answer questions?

Multiple revenue accounts may work for a for-profit company. However, the issue of accountability still exists with multiple revenue accounts.

We only touched on oil changes, brake jobs, and engine repair before, but there are a lot of services that a garage does that would quickly become unmanageable. Let’s name a bigger list of car services and start outlining the problem. Using this list let’s set up multiple revenue accounts for each service.

Car garage services examples

- Oil changes

- Brake jobs (rear, front, or both)

- Engine repair

- Fuel filter

- Transmission oil and filter change

- Drive axle replacement

- Differential replacement

- CV boot replacement

- Air filter change

- Inspection

- New tires

- Tire rotation

- Shocks and strut replacement

- and so on

As you can see this is just a small sampling of what a car garage does. But if the garage did set it up this way they could answer the questions (#1 – #5) listed above. But let’s throw another wrench into the mix and pose a few other questions.

- What if the company wanted to see how much they made on brake repairs for Chevys versus Fords?

- Or how much they are making on Ford oil changes versus Dodge oil changes to compare which manufacture was more profitable?

- Or how much revenue did we make working on Chevys vs Fords in general?

The above multi revenue structure also fails when trying to answer these three questions. What it comes down to is, you can’t create enough revenue accounts to handle each scenario An additional level is required beyond the basic revenue accounts. A for-profit accounting software system simply isn’t created from the ground up to do this.

Is there another way to use multiple revenue accounts?

The only way to try to answer these last three questions is to have revenue accounts for each car manufacture along with the performed service. Thus it would explode the revenue accounts a hundred times larger than the previous structure. It would look like this for just two services — oil changes and brake jobs. Imagine how large just the revenue section of the chart of accounts would be when you add in all the other services with sub-accounts for each car manufacture.

CoA layout example

- Oil changes

- Chevy

- Ford

- Dodge

- Chrysler

- AMC

- Jeep

- GMC

- Import

- Toyota

- BMW

- Nissan

- and so on for each car manufacture.

- Brake jobs (rear, front, or both)

- Chevy

- Ford

- Dodge

- Chrysler

- AMC

- Jeep

- GMC

- Import

- Toyota

- BMW

- Nissan

- and so on for each car manufacture.

- And so on for each service.

Using the above structure, the auto garage can answer the previous questions (#1 – #3) for each service type. However, as you can see having a large chart of accounts often becomes unmanageable for most organizations — for-profit and nonprofit. A structure where there are hundreds of revenue accounts makes even the simplest transaction difficult to enter. Then add in the scenario where a car receives an oil change and a brakes job which requires splitting the entry into two or more revenue accounts, and the transaction becomes increasingly difficult.

For-profit companies are focused on making money. They are not interested in accountability, unlike churches and other nonprofits. For-profits are able to use limited accounts to track their revenue and expenses, thus stressing profitability over accountability. The sheer amount of revenue accounts needed to demonstrate accountability is why churches use fund accounting. Fund accounting allows them to simplify their Chart of Accounts while maintaining transparency to their donors.

How do car manufactures relate to fund accounting?

Glad you asked. Let’s use the revenue accounts oil changes, engine repair, brake jobs, fuel filters, and so on. We showed 13 of them earlier. We still want to know the car manufacturer for each type of service revenue, but we saw how this exploded the revenue accounts into hundreds of accounts.

Let’s use 11 car manufacturers as listed earlier in conjunction with the same 13 revenue accounts. In other words, we don’t repeat the car manufacturer for each service like before. We use the same 13 revenue accounts, and tag the transaction with a car manufacture — Ford, Chevy, and so on. This is illustrated in the third column in the table below. Let’s see how that plays out using a table for a transaction.

| Account | Amount | Car Manufacture |

|---|---|---|

| Checkbook (DR) | $ 650.00 | Chevy ($625) Dodge ($25) |

| Revenue – Brake Jobs (CR) | $ 525.00 | Chevy |

| Revenue – Oil Change (CR) | $ 100.00 | Chevy |

| Revenue – Oil Change (CR) | $ 25.00 | Dodge |

| Account | Amount | Car Manufacture |

|---|---|---|

| Checkbook (DR) | $ 1350.00 | Ford |

| Revenue – Brake Jobs (CR) | $ 425.00 | Ford |

| Revenue – Oil Change (CR) | $ 125.00 | Ford |

| Revenue – Engine Repair (CR) | $ 800.00 | Ford |

Note: We did split this into two tables to make it easier to see. However, this could all be done in one large transaction, hitting each revenue account and tagging the appropriate car manufacture.

Answering the questions using fund accounting software

Can we answer all the questions we need when we use this tagging system? Short answer – Yes. Let’s check out the answers below.

- How much money did we make on oil changes today?

- Ans. $ 250.00 for oil changes.

- Or just brake jobs?

- Ans. $ 950.00 for brake jobs.

- How much did we make in engine repairs all year?

- Ans. $ 800.00 for engine repairs.

- Are we making more money on oil changes or brake jobs?

- Ans. $ 250.00 oil changes vs $ 950.00 brake jobs. Brake jobs make more money.

- How about engine repair revenue compared to oil changes?

- Ans. $ 800.00 engine repair vs $ 250.00 oil changes. Engine repair is more.

- What if the company wanted to see how much they made on brake repairs for Chevys versus Fords?

- Ans. $ 525.00 for Chevy vs. $ 425.00 for Ford.

- Or how much they are making on Ford oil changes versus Dodge oil changes to see which ones are more profitable?

- Ans. $ 125.00 for Ford vs. $ 25.00 Dodge. Ford oil changes are more profitable.

- Or how much revenue did we make working on Chevys vs Fords in general?

- Ans. $ 625.00 for Chevy vs $ 1350.00 for Ford. Fords make more money.

As you can see by tagging these entries you remove having to duplicate revenue accounts to track the additional information. Additionally, you are able to answer all eight questions, we couldn’t earlier with one or multiple revenue accounts.

Tying the car manufacture example to fund accounting.

Before we transition to the nonprofit sections let’s see how the car garage example helps us understand fund accounting.

Let’s replace the car manufacturers we used above Ford, Dodge, and Chevy with funds, such as General Fund, Youth Fund, and Building fund. And the Revenue accounts, Oil Changes, Brake Jobs, and Engine Repair will now become Donation Revenue, Daycare Revenue, Room Rental Revenue, and so on.

Receiving Donations in a Nonprofit Organization

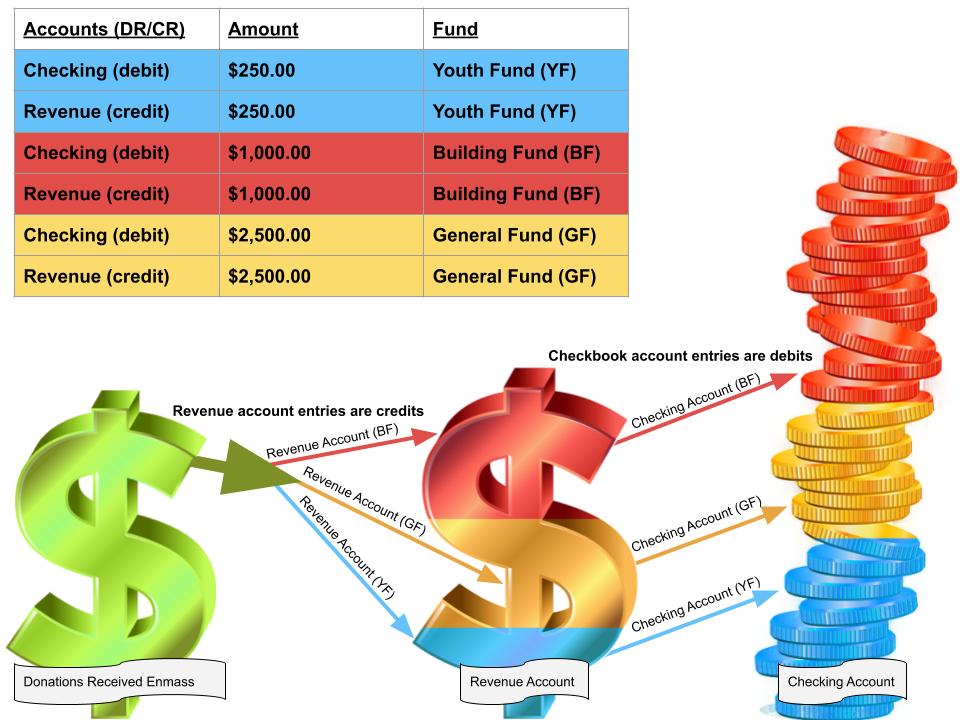

The illustration below shows how the lump sum of donations is eventually segregated into three funds — Building (BF), Youth (YF), and General (GF) fund. The lump sum of donations, represented by the green dollar sign, comes into the organization as a total deposit into the bank account. Banks do not care about the church’s accounting as far as funds and accounts, thus they only need to know the total amount deposited.

However, the church needs to know a little more than just the total deposited amount at the bank. The church needs to know how to breakdown the total deposited into separate categories or funds, illustrated in the colored dollar sign. This colored dollar sign illustrates each fund by using a different color — red, gold, blue, within one revenue account.

Using one revenue account the church makes three entries using the various amounts for each fund — ie. $250.00, $1,000.00, and $2,500.00. See the revenue entries in the illustration’s table. These entries would be tagged with the various fund notations, such as BF, YF, or GF. We use fund names here instead of the car manufacturers Chevy, Dodge, and Ford.

Why three disbursements instead of one totaling $ 3,750.00?

This separation of monies is so the church can report on the totals for each ministry. In this scenario, those ministries are the General Fund, Building Fund, and Youth fund. More importantly, is that the money must stay separated throughout the church’s accounting as it travels through the revenue account, into the checkbook, and out through the expenses. Another consideration is that churches must follow FASB which states monies must be kept separate.

Isn’t that more work making all these additional disbursements and/or transactions to know how much the one fund received versus another fund? No.

Why? When using IconCMO’s donation and accounting package, the donation system updates the accounting module automatically. Good fund accounting software, like IconCMO, can apply the donations to their donors, then automatically make the accounting transactions on the revenue/checkbook side, saving time and work.

What about the offsetting entry into the checkbook?

The stack of coins in the illustration represents the church’s checkbook. Just like the revenue account is spilt between three funds, the checkbook is as well. The difference is that the checkbook holds a balance that goes up and down as money is received or spent. Revenue accounts do not hold balances. Revenue accounts only track how much money was earned by that particular line item, then zero out at the beginning of the fiscal year.

In fund accounting, the checkbook has what we call mini-balances within it. These aren’t sub-accounts of the checkbook. Checkbooks should never have sub-accounts in any fund accounting software. These mini balances are representative of the funds and their balances.

In double entry fund accounting, you must apply a debit, a credit, and a fund. The credit increasing the revenue account income. The debit increases the dollar amount in the checkbook and the fund assignment earmarks the monies and increases the mini-balance in that particular fund. Let’s review how this looks before and after the donations are entered into the checkbook, in the table below.

Note: We use the same color scheme as the previous illustration to depict the funds clearly.

| Fund | 1. Checkbook Balance – Before | 2. Add Donation In | 3. Checkbook Balance – After |

|---|---|---|---|

| General Fund | $8,100.56 | $2,500.00 | $10,600.56 |

| Youth Fund | $1,125.36 | $250.00 | $1,375.36 |

| Building Fund | $50,500.60 | $1,000.00 | $51,500.60 |

| Total For Entire Checkbook | $59,726.52 | $63,476.52 |

Walk-through example of the Youth fund.

Let’s look at one example in the table above as each fund will follow the same method. Let’s first review the left column (#1) of numbers. The youth fund currently has $ 1,125.36 in the checkbook. This is the Youth fund’s current mini balance in the checkbook. In other words, out of the entire amount of $ 59,726.52 in the checkbook, the Youth fund owns $ 1,125.36 of it.

The middle column lists the donations that were received. These aren’t balances in the checkbook. The #2 column numbers are the amount of money coming into the organization as donations via one of the funds and through the donation revenue account. The Youth Fund started with $1,125.36 and is being increased by $250.00.

The last column of numbers (#3) shows the ending results after all the revenue is added to each funds’ checkbook mini balance. The new Youth fund’s mini balance in the checkbook is $1,375.36, noted in the last column of the table for the Youth fund. The General Fund increased $2,500.00 and the Building Fund increased $1,000.00 for a total increase of $3,750.00 for all funds.

Summary of Accounting Software for Nonprofit vs For-profit

We went over how the money comes into an organization in for-profit and nonprofit scenario. In both of these scenarios, we see stark differences in how each type of organization operates. These differences are too hard to overcome when the accounting software is not defined from the ground up to handle the differences. When an organization uses the wrong tools, then workarounds are used resulting in too many revenue accounts, multiple checkbooks, classes, and so on. In the nonprofit area, these workarounds are covering up a more serious problem and should be avoided at all costs.

We showed how a for-profit system can’t answer some of the most basic questions beyond the organization’s profitability. For-profit systems can’t drill down on the detail and get specific information in a meaningful way. These for-profit systems can’t answer the simplest questions like how many Ford oil changes compared to Chevy oil changes the company has completed? Which service is the most profitable after all expenses are paid? For-profit accounting software simply fails in these and many more areas.

Fund accounting on the other hand can answer questions in finer detail, as we have shown using the eight questions. We proposed the same eight questions in the for-profit and nonprofit accounting sections and only the nonprofit scenario can answer them. The reasoning comes down to the goal of the accounting software. One is geared towards the accountability of resources and the other is the profitability of the organization as a whole.