This post was last updated on November 22nd, 2021 at 12:56 pm.

Church financial statements are the reports churches should be reviewing on a monthly basis. While church budgets may be important, this is only a best guess as to what will happen throughout the year. More time each month should be dedicated to reading through financial statements of what has happened rather than the budget.

Many leaders will say “but I haven’t spent my budget” or “how much is left to spend in this xyz ministry”. These types of questions reveal an organization that focuses too much time on budgets and not enough time on understanding financial statements. Simply stated — the budget numbers set at the beginning of the church’s fiscal year (i.e. January) aren’t the last word when looking at spending in August’s monthly meeting, eight months later.

Here’s the truth. The budget can say whatever you want, but if you don’t have the money to spend — you can’t spend, or worse yet, you go into debt. This is the case with your own home’s budget (i.e. checkbook,)when the money isn’t there, you can’t go out and spend $150.00 on groceries. So what reports give you the most accurate picture for these monthly meetings?

Your 30-day free trial of IconCMO is ready!

For future reference, an email with your log in credentials is on its way to your inbox. If you do not receive an email or have any other questions, please contact our sales department at 1-800-596-4266 or sales@iconcmo.com using the following account number: .

An email with your free trial is on its way to your inbox. In the meantime:

If you do not receive an email or have any other questions, please contact our sales department at 1-800-596-4266 or sales@iconcmo.com using the following account number: .

Let’s explore why financial statements are better than budget reports.

Why Church Budgets Fail

The first problem with budgets is that they’re set at the beginning of the fiscal year. Throughout the year the budget report will show the amount spent and compare it to the numbers set at the beginning of the fiscal year. As good as these numbers are, it fails to recognize the unforeseen expenses that pop up and can affect budget numbers. When this happens the budget typically isn’t updated across the board to limit spending in the next few months. Often times budgets are treated as a ‘set it and forget it’ kind of process.

When budgets aren’t updated, ministry leaders still assume they have money, but they don’t. Or the church may not have taken in enough revenue yet to cover the budget line item that you set in January. An example of the latter is, let’s say you budgeted for a roof repair of $1,000.00/month. Later you find out the contractors are doing the roof in August. You still need $4,000.00 (Sept – Dec) in revenue that hasn’t been collected. How will you pay the contractors now when you haven’t received all the money yet? Some budget lines will have to give up their resources in the short term to pay the contractor.

Budgets are like the old atlas road maps that we used to keep in our cars- they’re outdated the moment you buy them. On the other hand, financial statements are like having a real live GPS device that beeps and finds an alternative route when you take a wrong turn. Given this analogy, which one do you believe is better — the outdated road maps or the always updated GPS?

Church Budget Methodologies

Let’s first talk about budget methodologies to understand how budgets work. There are several budget methodologies called the — Zero-Based Budgeting approach, Rolling Forecast, or Annual Budget. These budget methodologies all have issues when it comes to giving church leaders the right information to make decisions. This is why financial statements should be used and understood — and not budgets. We’ll discuss financial statements later in this post.

Zero-based budgeting

When a new period starts, each church function (i.e. ministry) begins at zero, then is analyzed for its needs, and the budget is adjusted for any cost above zero. The one thing the zero-based budgeting methodology (ZBB) does well, is there’s a justification process each time. It keeps the church from using the same numbers ‘as last year’. It ensures the church can keep illustrating that each budget line makes sense in regards to monthly/annual spending. So where does it fail?

Zero-based budget failure

What it does poorly is communicate to church leadership that xyz ministry has so much money to spend, even when the checkbook can’t cover it. For example, the Youth ministry in January is told they have $1,200.00 for the year after they illustrated their needs. However, the Youth ministry, many times believe, they have this full $1,200.00 dollars right away which is false.

The church has to wait for the donations throughout the year to allocate to the Youth ministry. So let’s say the church leadership instead advises the Youth Ministry you have $100.00/month. There can be a couple of hiccups with this as well. What happens when the donations for the Youth ministry don’t come in until February and you were told you have $100.00 in January? Sure, the General fund could subsidize it for the first month but that’s self-defeating. How do you know the General fund has the money? So this budget methodology fails right away.

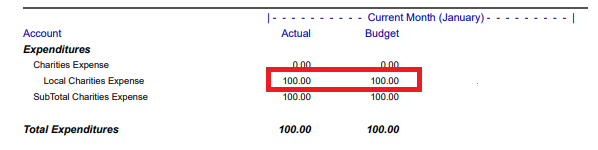

Below is a representation of a budget report. The budget and the actual columns show $100.00 each. This gives a false impression that the Youth Fund (ministry) is doing fine since $100.00 was allocated and then spent. Nowhere does it show that the money was ever there to spend in the first place. The church is assuming they received the full amount of donations to cover the $100.00.

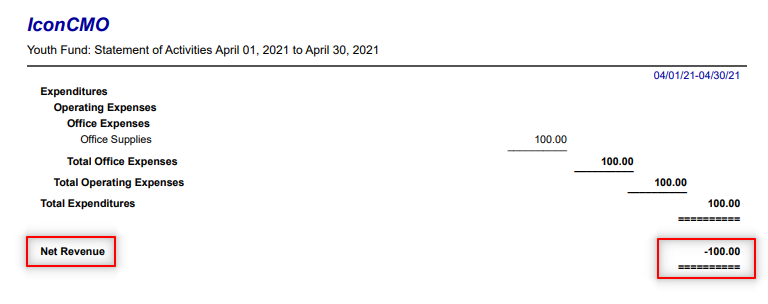

Financial statement solution

How do financial statements fix this problem? The expense is applied to the Youth ministry fund, thus the fund’s financial statements will show a negative net asset (fund balance.) Having a negative isn’t a good scenario, but it gives church leaders better information than the budget. It alerts them just like the GPS device, to say there is an issue here — check it out. In this case, having a negative number on the report is a better indicator than what we see above where the two numbers are the same which gives no alert to a problem. Let’s see what it might look like below.

By using financial statements leaders can ask questions like do/did we have revenue coming in to cover this? Should the revenue already be there – why or why not? Do we have to adjust our spending for the upcoming month because of this shortfall? As you can see the financial statements show a better view of the church’s financial health.

Rolling forecast budgeting

The rolling forecast budgeting is better than the Zero-based budget when done correctly. It requires periodic changes to the budget throughout the year. Typically this is completed at the month-end review, at a minimum.

Rolling forecast budget failure

The periodic changes that this budget methodology requires has a huge weakness. Practically no organizations change their budgets throughout the year. Once they enter their numbers they are unchanged. In other words, they don’t update their budget numbers which this budget type requires. The only time this rolling forecast budgeting methodology can be of any help is if this method is used correctly. Specifically, the rolling forecast budget has to be updated monthly to ensure everything is adjusted as needed and designed.

Another weakness is the updating budget numbers themselves. Because the numbers change, the church doesn’t know what the original budget numbers were unless they keep a hard copy somewhere, which is unlikely. When the numbers are updated the old numbers are simply overwritten with no historical context kept. It comes down to the one strength that this budget type has, which is also its own weakness — changing numbers that destroys the historical context of those numbers.

Financial statement solution

Because financial statements give updated information based on any date you use, you can always get the current or historical amounts. Numbers are not overwritten. This gives the church leaders information that budgets can’t provide throughout the year. The numbers are automatically updated as transactions are entered with no work involved. They can run these reports based on funds where they can drill down to see one ministry’s spending and revenue.

Annual budgeting

This budget methodology is a 12 month period that covers the fiscal year. It’s very similar to zero-based where the numbers are set and typically never changed even as circumstances change. Rarely can a church go a whole year without things coming up and the budget set in January is no longer relevant in August. In this budget methodology, the church copies it from one year to another year and doesn’t start at zero.

Annual budget failures

The annual budget failure is similar to the zero-based budget methodology but takes it a step backwards. Because this one rolls over from year to year, it doesn’t force an up-and-close review of each line item. If you remember the zero-based, one would zero out the entire budget and then input the numbers one by one for each line item. It also has the other issue in that the budget is not updated when things happen. In summary, this one has two primary issues – rolling the numbers from one year to the next without any justification, and not updating those numbers throughout the year when changes occur.

Financial statement solution

On a financial statement, the numbers for expenses or revenues never ‘roll over’ from one year to the next. This is by design in accounting systems. The general ledger accounts by default, are zero at the beginning of the fiscal year. Financial statements also do not suffer from the ‘updating numbers’ issue throughout the year as we discussed previously. Financial statements always show the actual amounts of where the organization is at, not some best-guessed numbers made in January.

Budget methodology summary

All of these various budget methodologies have flaws either in the way they are set up or throughout the year with no updates to them. None of this to say that the church should abandon budgeting as a tool. What leaders need to know is budgets are tools, and there must be a greater understanding of financial statements. If churches understood financial statements as well as they can create budgets, they would be financially better off. During audits, churches should remember that budgets are not the reports that are requested — financial statements are.

The Church’s Secret – Reading Financial Statements

A church’s secret to success is understanding its financial statements in a detailed manner and adjusting to those numbers as needed. Churches spend more time each year creating a budget than reading financial statements. For example, church leaders may spend ten minutes during a monthly meeting going over the financial statements. But spend many hours, if not days, completing the budget.

A good way to prove budgets don’t work — is if the church is scratching their head at the end of the year, wondering why they spent more than their budget advised twelve months ago. If budgets work, then there should be no surprises at the end of the year.

So what can the financial statements show you via analysis? Let’s first look at the P&L sheet, which is called the Statement of Financial Activities in church accounting. Then we will go over the balance sheet, called the Statement of Financial Position.

P&L Sheet

What can this report show us? Let’s first start with what’s on the report. It will show the revenue and expenses that happened within any date range. There must always be a date range since revenues and expenses do not carry balances – i.e. they don’t roll over each year. Asset and liability accounts are not shown on this report — i.e. checkbook balance.

In monthly meetings, this report will typically list all the activity of the month. In church accounting systems that are fund-based and compliant can run these reports by the fund. This allows the leaders to see each function area of the church and focus on their expenses and revenues, separately from other ministries.

What can it tell us?

What can we see from this report? First, the report will show a net revenue towards the bottom. What this shows is, if that number is positive, the church took in enough revenue to cover the expenses within that church’s function — i.e. Youth, Missions, General Operating, etc. If it’s negative, that’s a red flag and questions should be asked.

The next question is if the net revenue is enough to sustain the church’s function in the future. After all, you could have more revenue coming in than expenses going out, but what about the long term? Did this month have low expenses for some reason, thus the revenue was just enough to show a positive? To see over a longer date range the P&L report can be run for the year to date (YTD), date range. Is the net revenue still positive on the YTD report? If so, by how much, and is that a comfortable amount? Budget reports have a hard time answering these forecast questions.

Checking expenses

The next thing to review on this report is to ensure you don’t see any items that the fund should not be paying for. For example, on a Youth fund report, you probably would not expect to see it paying for a utility bill because the General (or Operating) fund pays for that expense. Is there anything odd on the report that shouldn’t be there? You would be amazed by how many expenses are coded wrong in an accounting system.

Another item to consider, especially in the General (Operating) fund, is if any expenses seem to be too much. Maybe the snow removal company’s price has increased for the last 5 years and it’s out of control now. Would it be worth going to get a few estimates from others and change to a new contractor? What about the plumber, electricians, and general maintenance cost? On the flip side, maybe you have a missionary that hasn’t had an increase in their living expenses for years from the church. Should that happen at this time?

Lastly, the P&L should be compared to the budget numbers that were set. While the P&L doesn’t include budget numbers since they are best guesses and not factual numbers, this would require looking at both a budget report and the P&L together. It’s worth noting that both the P&L and budget report should be run by the same fund(s) and time periods. When comparing the numbers you want to ensure you are on track with spending and incoming revenue.

Balance Sheets

What can a balance sheet show us? Let’s first discuss the proper terminology in the church industry for the balance sheet report — it’s called a Statement of Financial Position. For our purpose here we will use the shorter name, balance sheet, for brevity.

Next, let’s understand what is on this report. This report shows the balance sheet accounts that roll over each year. Accounts such as checkbooks, savings, accounts receivable, and liability accounts- like loans. Collectively these are called balance accounts in accounting. Additionally, this report uses an end date – typically the end of the month instead of a date range.

Why isn’t a date range used? The balance sheet accounts take into account every transaction from the beginning of time to the end date that was entered. Conversely, revenues and expenses on the P&L sheet start over each fiscal year. The checkbook balance today has to reflect the transactions (deposit and withdraws) from 10 years ago, to arrive at the right balance.

What are some of the things to look at on a balance sheet report?

First, the report can give us the balance of the checkbooks by fund — i.e. the functional areas of the church. When reporting by fund, you will only see the balance of that fund in the checkbook. The total checkbook balance is not shown and is intentional. By showing only the fund’s checkbook balance you can see the remaining balance for that area of ministry instead of the entire church.

The next thing the balance sheet can tell us is — what is the total of net assets? The net assets are the cash and other assets on hand subtracted from the liabilities. Most funds don’t have any liabilities thus the net asset amount is the same amount as total assets.

For funds like the Operating fund, there typically are liabilities involved. It gets a little trickier when liabilities are present. Because loans can have large balances, often much larger than cash on hand, the church leaders need to know how to decipher the numbers and keep them straight. One way to do this is to keep building assets and their associated loans in their own fund and pay the loans from that fund. It’s typically called a Building Fund. This keeps the loans separate from the General fund which deals with the immediate needs of the church.

Current ratio

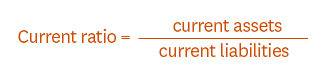

Simply stated this ratio shows the amount of liquidity available to pay for current liabilities over the next year. The optimum ratio should be 1.5 to 2.0 and we will call this the green zone. It can be higher than 2.0 which is better. However, less than 1 spells trouble — the red zone. Between 1 and 1.5 the church could be in trouble — the yellow zone. How do you figure out the current ratio?

How do you figure out the current ratio?

Add up all cash and cash equivalents – i.e. cash on hand, accounts receivable (less than one year), money market accounts, marketable securities, and so on. Think of any assets that the church could get its hands on fast and convert into cash. Now add up all the liabilities that are due within one year. Things like loan payments, accounts payable (AP), salary, and tax payable. This also includes expenses (i.e. electricity, water, etc.) that you have not paid but aren’t in AP, yet.

Here’s the formula to use.

Let’s use two examples.

- Church has $100,000 in cash. They have current liabilities (loans) of $12,000 and the church has total expenses for the next 12 months of $30,000. This would give a 2.38 for the current ratio. This church has enough money to cover its expenses for the next 12 months.

- The next church has 100,000 in cash. They have current liabilities of 60,000 and the church has total expenses for the next 12 months of 12,000. This gives you a ratio of 1.38 which is less than 1.5 minimum standard. This church could have problems meeting its obligations for the next year.

Note: In these two examples it’s interesting to note that the church with higher annual expenses and lower debt is better off. It’s often thought that high expenses are the problem but in this case, it was actually the high debt load that made one organization worst than the other.

Another item to look at is huge cash piles in the checkbooks. While most people think huge cash piles is a good thing, it can also be bad. It could mean the church probably isn’t using its resources wisely by either not investing it, not moving it to a money market account for a large purchase later, or dedicating more to ministry to further their mission.

Lastly, the balance sheet reports can show if the church’s accounts receivable are increasing by looking at this figure month to month. This is very common in churches that have daycares or schools. When this number is increasing, it means the church is not collecting the money that it’s owed in a timely manner. In a perfect world, this account should zero before the church sends out the next round of invoices, but that rarely happens. If this number is growing each month, that means the organization has a poor collection plan in place for its debtors and it should be reviewed.

Summary

This blog post shows what can happen when an organization relies on budgets more than financial statements. It shows why churches should spend more time understanding their financial statements, instead of budgets. Budgets are only a tool. Additionally, churches put an inordinate amount of time into budgets once a year, and hardly ever revisit it throughout the year. Conversely, church leaders need to put in as much if not more time into reading and understanding financial statements than budgets. We also went over multiple areas of each financial statement that the church should pay attention to.

Leave a Reply