This post was last updated on September 26th, 2022 at 04:59 pm.

This is the second of our four-part series on successful church fundraising. (See Part I, Part 3, Part 4)

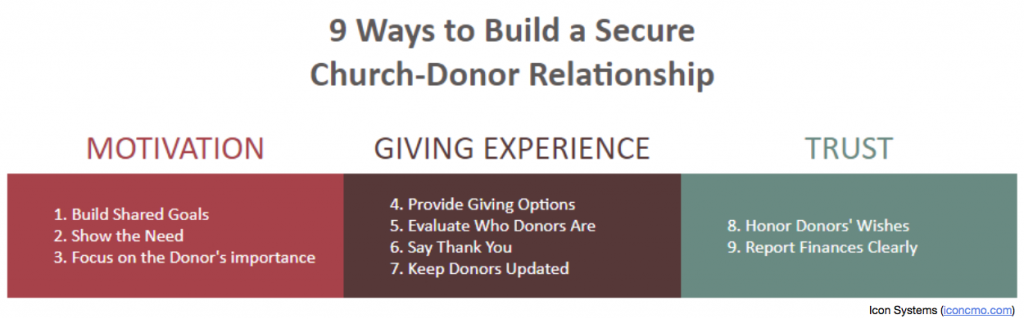

For this post, we’ll zoom in on the first principle of fundraising: motivation.

Motivation

How do you convince donors that your project is worth giving to?

1. Lay the groundwork to cooperate toward a clear, shared goal.

First, a church organization and its congregation and donors need to share the same priorities. They need to have one vision of what the church is about. It takes work and communication to cultivate a common vision, but it’s an essential first step to raising money. Church leaders who simply make up their own minds about spending priorities and then seek buy-in from the congregation, well, they’ll have an uphill climb.

Working together from the start is a great way to respect and value the donor. Think about it; would you be more likely to donate to your church’s fundraiser if you had some part in prioritizing and organizing it? That’s why you need to reach out to your members. Get together and start sorting out the church’s vision and how the church will collect and spend money.

In The Dynamics of Church Finance, James D. Berkley explains some ways to get a congregation’s collaborative circuitry firing:

- Create a church fundraising policy statement. This statement lays out how the church introduces and approves fund raising projects, what activities meet the church’s identity and purpose, what activities don’t, and so on. It settles certain questions so that they don’t need to be argued or guessed at over and over.

- Create a list of priorities. Start a committee or congregational meeting with a blank sheet of paper and a simple question: if the church could only fund 10 things, what would they be?

Based on my experience in church meetings, I’m especially fond of the second point. Better to get everyone’s thoughts out in the open and nail down priorities before starting a project than to wait for all those feelings and conflicts to bubble up to the surface later. And they will.

2. Show the need. Don’t just talk about it.

“Show, don’t tell.” That’s what James Schaap would say in nearly every class in his fiction writing course.

Before I heard this bit of wisdom, I never noticed how often fiction writers settle for just telling story elements to the reader — “The losing pitcher was depressed” — and how much more potent their writing is when they show the reader:

“The losing pitcher sat motionless on the bench by his locker, his chin resting between his knuckles. He gazed at his dusty green cap as distant cheering echoed down the hall.”

Vivid imagery lights up parts of the brain that mere facts just don’t, and the same goes for vivid storytelling. A picture, a story, personal details — these give our imaginations, our memories and our internal motivational instincts something to latch onto.

Deborah Small cites a study, that her and other colleagues George Lowenstein and Paul Slovic showing that subjects who heard specifics about an individual’s life could be over twice as generous as subjects who were given statistics.

In fact, study subjects were actually more generous in response to individual details than they were to details plus statistics. I’m not recommending ditching stats and figures, but that’s an interesting datum.

3. Focus on your donor’s role in addressing the need.

When you show the need for the fundraising effort with real stories, remember: respect and value your donors.

Megan Donahue writes in “Storytelling Should Fuel All Your Fundraising” that a crucial element of the story is to show the donor how he or she can play a meaningful role in improving the person’s life or moving the project forward. She writes, “Humans love stories. Stories engage our brains and emotions.”

She writes further about how to focus on the donor “These days, donors want to feel included. They want to make a difference, and for their personal donations to matter. So you need to tell stories that bring them into your world and demonstrate their impact.”

“The word ‘donate’ just doesn’t have the same oomph as ‘give clean water’ or ‘feed hungry children’.”

For one thing, ‘donate’ doesn’t place the donor in the role of the hero as well as specific verb-impact phrases.”

Once the project is in progress, keep telling the story and showing donors that their donations are important.

Leave a Reply